The British Government has announced A$63 million scheme to teach robots “empathy” to care for people in care homes in an attempt to fill the gap created by shortfalls in adult care provision.

Care robot technology is being currently developed in the private sector, but the Government is worried that robots will struggle to care for people in homes because they lack a human touch.

The fund will be distributed to universities and other research groups, who will develop guidelines to help robots make human-like decisions when caring for older people.

Robots will be required to make decisions that prioritise the care of humans. For instance, if a person was to fall while carrying a cup of tea, the guidelines would require robots to help the fallen person before clearing up mess.

Adult care crisis

Earlier this year, care chiefs warned tens of thousands of older and disabled people at risk of being denied basic support because of shortfalls in adult care provision in the UK.

Likewise, Australia is facing a carer shortage and, as the percentage of the Australian population aged over 85 is set to double by 2066, the problem shows no signs of going away.

According to Deloitte’s report, “The Economic Value of Informal Care in Australia”, there were 2.7 million unpaid carers in 2015 and the replacement value of the unpaid care provided was $60.3 billion – which is over $1 billion per week.

Only 272,000 carers are under the age of 25, according to the Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, whilst the average age of a primary carer was 55. The survey also found that over half of primary carers provide at least 20 hours of care per week. And according to Deloitte, carers provided an estimated 1.9 billion hours of unpaid care in 2015.

Robot solution

It is thought that robots could be a solution to the care crisis, making care for older people easier. Estimates suggest autonomous technology could give older people in care an additional five years of life.

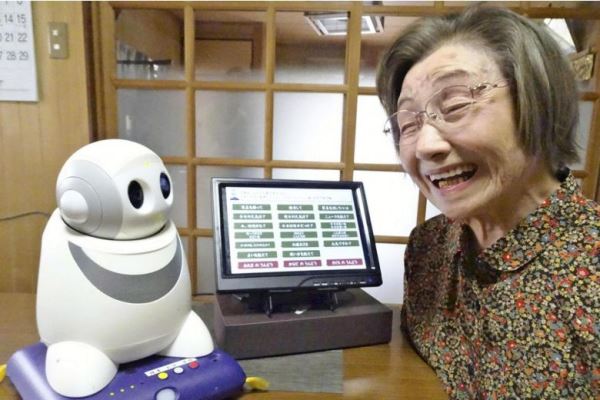

Robot carers and robotic companions have already been used in Japan, which is predicted to have a shortfall of 370,000 caregivers by 2025, to help lonely or dependent older people.

Takanori Shibata, a Japanese scientist, has developed a “therapeutic robot” in the form of a robotic harp seal with a Canadian accent. It had been found to reduce patient and caregiver stress by imitating the relationship between a patient and caregiver.

Developing robots to assist elderly people in care is a major area of development for British robotics companies. The Bristol Robotics Laboratory has developed a robot that can help with tasks like ordering the shopping and reminding elderly people when to take their medication.

But experts worry that robotic carers could never fully replace humans, since they are unable to replicate the companionship and emotional care that flesh-and-blood caregivers can provide. Autonomous robots also have navigation issues. More basic technology such as robotic cleaners find it difficult to negotiate users’ houses reliably.

While self-driving cars are relatively well-developed, other uses of autonomous robots such as care and surgical robots are still in development. But within a 20-year time frame, the Government expects self-driving cars, robotic carers and surgical robots to be a common part of everyday life.

However, Labour believes the plan would "do nothing" to solve the care crisis: “Social care is in crisis and this needs an urgent solution. Boris Johnson promised this on the steps of Downing Street but is completely failing to deliver what is needed,” Barbara Keeley MP, Labour’s Shadow Cabinet Minister for Social Care says.

“After years of delay, this Government needs to act and put forward their plans for social care. Projects like this do nothing to ensure that the 1.4 million older people who are going without care get the care they need.”